The Economist / Special Report / Muslims in the West

By Nicolas Pelham

Muslims have had a significant presence in the West for three generations, says Nicolas Pelham. Though both sides remain wary, they are getting closer Islam in the West

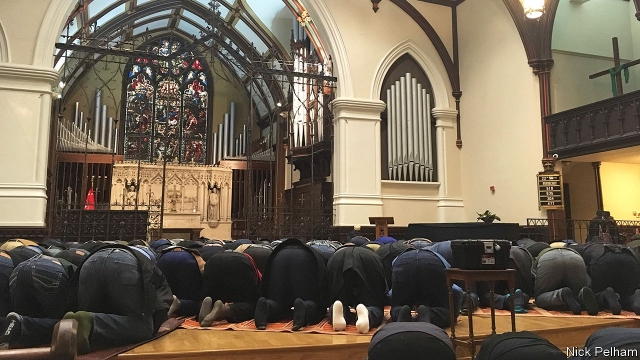

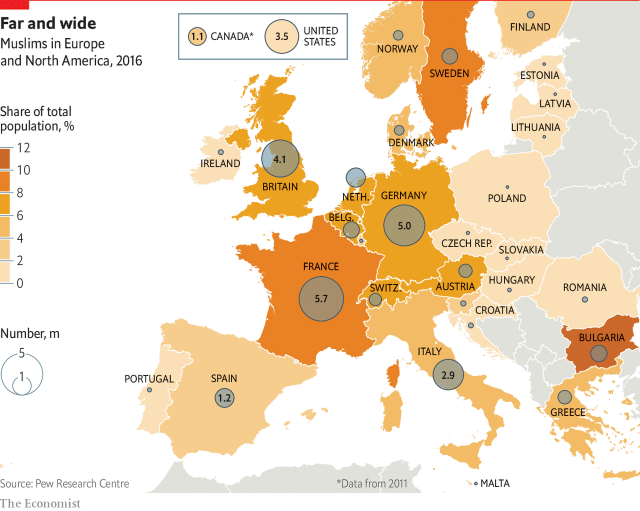

Every friday lunchtime, Washington’s Church of the Epiphany near the White House turns into a mosque. Hundreds of Muslims prostrate themselves in the direction of Mecca on carpets spread on the ground (pictured). The congregation includes Homeland Security and fbi agents, State Department bureaucrats and a posse of lawyers from the Department of Justice. The imam is a Treasury official. His sermons steer clear of politics. America’s Muslims have come a long way since some of their ancestors arrived as slaves from West Africa in the 16th century. From the late 19th century to the 1920s a wave of well-off Arabs came to study and stayed on, entering the ranks of America’s middle class. In a nation of immigrants, Muslims found it easier to fit in than in Europe with its more settled population. Except in a few cities such as Dearborn, Michigan, Muslims in America are thinly spread, totalling about 3.5m, or 1.1% of the population. Europe’s relationship with Islam has been longer, deeper and more conflicted. The religion had previously entered Europe in the eighth century in Spain under a caliphate and again in the early 14th century in south-eastern Europe under the Ottomans. Both times it came in by the sword and was driven out more than half a millennium later. In the 20th century the Muslims in Europe were different from America’s, too. Millions remained after the Ottoman armies were defeated, and new ones were brought in as soldiers and workers. European powers drafted some 3.5m Muslims from their colonies to fight two world wars. Most went home afterwards, but more arrived to repair the war damage. In the two decades after 1945 western European governments recruited hundreds of thousands of migrant labourers from farflung places.

Britain brought in Pakistanis from the Kashmiri mountains and the highlands of Bangladesh’s Sylhet; France turned to its north African territories; and Germany imported workers from Turkey’s Anatolian hills. They were expected to leave when their work was done, but instead fetched their families. Germany took its time to grant them and their German-born children citizenship. More recently an outpouring of asylum-seekers from the Muslim world’s many conflicts has changed the demography. Between 2014 and 2016 alone about 1m migrants arrived in Europe, most of them Arab. Germany took in half of them. They asked for workers, and people came Leaving out Russia and Turkey, Europe is now home to about 26m Muslims, who account for about 5% of its population and are typically much younger than the locals. In many European cities Muhammad (in its various spellings) has become the most popular name for a child. Precise numbers are hard to pin down. Besides, Muslims are not a homogeneous group; they differ by religious practice, culture and ethnicity. Their experience also varies from country to country. British law protects diversity in religion and practice, whereas in France the display of religious symbols, including the veil, is banned in most public institutions, including schools. Yet French Muslims tend to be less religious than British ones, and non-Muslims in France are happier to have Muslims as neighbours and more likely to marry one.

In some ways the 20th-century wave of Muslim arrivals in the West has done remarkably well. Many of them went from the mostly illiterate edges of the Islamic world to industrial cities. They often came from large families. Their children have gone a long way to closing the gaps in education, salary and lifestyles with their adopted countries. Muslims are also becoming increasingly prominent in Western politics. In November’s midterm elections, Americans voted two Muslim women, Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar, into Congress for the first time. London, Europe’s largest city, has a Muslim mayor, Sadiq Khan. The continent’s largest port, Rotterdam, has a Moroccan-born one, Ahmed Aboutaleb. And Muslims play a large part in Western entertainment, sports and fashion. But the past two decades have been marred by violence and fear, too. Since 2000 more than 3,670 people have been killed in jihadist attacks in the West, 2,996 of them in America on September 11th 2001 alone. Over the same period 119 people died in anti-Muslim assaults. Jihadists make up a minuscule fringe of Muslims in the West, but those terrorist attacks turned Islam into a looming threat in many Western minds. Far-right parties fed on, and fanned, such fears. Even short of violence, the relationship between Muslims

and their Western host countries was often wary or worse. America’s Muslims until fairly recently considered themselves a cut above Europe’s. They were more middle-class, more integrated and enjoyed a more harmonious relationship with their chosen country. But a combination of America’s involvement in the Middle East, the jihadist reaction to it and a concurrent surge of white nationalism has disturbed the harmony. In a survey in 2017, 42% of Muslim schoolchildren in America said they were bullied because of their faith. One in five Americans would deny Muslim citizens the right to vote. President Donald Trump encouraged such hostility during his election campaign, pledging a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”. Soon after coming to office he tried to impose a visa ban on six mainly Muslim countries. And last month he stirred fears of Muslim immigration again by suggesting that prayer mats had been left at the Mexican border where he wants to build a wall. This report will explore how Muslim identity has been moulded by external and internal pressures since the mass migration to the West began in the 1950’s. It will trace the impact of the laissez faire approach Western governments initially adopted to the incoming faith and then of increasingly interventionist policies as the Muslim population grew and the relationship became more troubled. It will explore how Muslim communities have responded to policies designed to aid assimilation or improve security. The report will also look at the generational shifts within Muslim communities as their members have adapted to life in the West. Flexibility and pluralism helped Islam flourish as a global religion for 1,400 years, but recently in the West Muslims have had to devise a theology for living as a small minority among non-Muslims, not as rulers. This is still a work in progress. The first generation of Muslim immigrants largely accepted the West as they found it and kept a low profile, unsure how long they would be staying. They brought their rituals and traditions with them and looked to their countries of origin to cater for their spiritual needs. Imams came from Turkey, north Africa and South Asia. Some Muslim countries funded the building and running of mosques. As ties with the West became stronger, those with the incomers’ countries of origin diminished. Religion became more important than ethnicity as a marker of identity. The second generation of Muslims in the West rejected the quiet and submissive faith of their parents and looked for preachers who spoke their language and understood their concerns, often online. They wanted a religion that empowered them. At the extreme end, a few embraced violence. Jihadists are overwhelmingly either second-generation Muslims or converts. A third generation of Muslim millennials feels more confident both of its Western identity and its Islam. It has the tools to negotiate politics and the justice system, and to interact with the establishment. Religion is increasingly becoming a matter of individual choice. The 10,000-plus mosques in the West represent the entire spectrum of Islamic belief and practice, from the Deobandis (see glossary) to women-led prayer. Many have left the faith altogether. Past and recent experience has made Muslims wary of taking their future in the West for granted. But if the mainstream prevails, they are about to embark on a new phase. Three generations after their arrival, they are fashioning a theology for highly diverse societies and secular systems of government in which Islam does not hold power. In short, they are building a Western Islam.

Influence from abroad

Soft power

Foreign funding of Europe’s mosques is a mixed blessing

The imam of Germany’s largest mosque (pictured) is struggling to fill it. It holds 1,200 worshippers, cost €20m ($22.8m) and was opened last September to much fanfare in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia, the German state with the biggest concentration of Muslims. But only a few dozen elderly men attend his Sunday noon prayers. It might help if the imam spoke German. But he is a Turkish civil servant, one of hundreds sent on three-year secondments by Turkey’s Diyanet Isleri Baskanligi (directorate of religious affairs). It runs Turkey’s 900 mosques in Germany and around 1,000 more in places from Macedonia to Maryland. Like official religious bodies in other Muslim countries, it builds and maintains flagship mosques to project its own national variant of Islam, keep its diaspora loyal and cement its influence in the West. When Muslim migrants first started to arrive in Europe, there were good reasons for Western governments to outsource religious provision to foreign ones. Most of the incomers were too poor to pay for imams, and the West lacked the skills to cater for migrants’ spiritual needs. Muslim governments had the religious institutions to do it. In addition to building and running mosques, the Diyanet and its local arm, ditib (see glossary in previous article), provided extensive support to communities, running football clubs, summer camps and a subsidised funeral service for Muslims across Europe. The arrangement seemed mutually beneficial. Western governments preserved their secular credentials, their budgets and, in many cases, the polite fiction that Muslim migrants were outsiders whose presence was temporary. In some parts of Germany and the Netherlands Turkey’s Diyanet was even asked to provide religious education for Muslims in state schools. Middle Eastern Sunni governments spread their own national creeds. Their agents also kept tabs on troublemakers. After the oil-price shocks of the 1970s, Saudi Arabia embarked on a programme for Muslim hegemony. Its fundamentalist Salafism unnerved some, but it had the petrodollars to finance the project, and it helped reinforce the defences against Iran’s call to revolution. The Muslim World League, the foreign arm of the Saudi religious establishment, built and operated large mosques abroad. They trained a new cadre of imams, offering lavish scholarships at the Islamic University of Madinah in the holy city of Medina, where 80% of the students were religious scholars from abroad. Muslim autocrats came to value the soft power they gained. Preachers from Saudi Arabia and Algeria delivered diatribes against the menace of democracy, which they castigated as a Western artifice against God’s rule. Egypt’s informants kept watch on the dissident Muslim Brothers who had been chased abroad. Morocco’s mosques promoted the authority of its king and “Commander of the Faithful” over rebellious Berbers from the Rif, many of whom moved to Europe. In recent years Turkey’s imams abroad have been praising the policies of their paymaster, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and sounding an Islamist note. Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and, to a lesser extent, Iran extended their influence in Europe by helping the 7m indigenous Muslims of eastern Europe recover from the ravages of communism and the Balkan wars of the 1990s. They set up universities and rebuilt hundreds of war-torn mosques. “These were European mosques, and not a single mosque was rebuilt by Europe,” says Muhammad Jusic of the Islamic Community, the Sarajevo-based organisation that manages Bosnia’s Muslim affairs. Mr Erdogan, in particular, is reaping the dividends from restoring Sarajevo’s Ottoman mosques. When he visited the city last year, Bosnia’s president, Bakir Izetbegovic, hailed him as God’s messenger. Rising jihadist activity in the West strengthened the case for tightening foreign-government control of the mosques. North African officials pointed to their centuries of experience in promoting moderate orthodox Islam. “Morocco guarantees the security of the religion and guards against those entering mosques to plant mines in the psyches of worshippers,” says Ahmed Al-Abbadi, who acts as the Moroccan king’s representative for religious affairs. But accomplishing this was sometimes hard. Foreign imams on short-term assignments typically did not speak the language of the country they were working in, and seemed more concerned about securing promotion back home than building relations abroad. They slowed down the integration of first-generation Muslim migrants to the West and failed to grasp the difficulties faced by the second generation. “Foreign imams don’t make inspiring role models,” says Khaled Abou el Fadl, an academic from Egypt who chairs the Islamic Studies programme at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The politics of religion

DITIB’s Turkish officials compare its mosques in the West to foreign-run churches, like the Russian Orthodox or Lutheran ones in the Middle East, but many of them appear to be increasingly used for political ends. Sermons reflect Turkey’s tilt from secularism to an assertive Islamism. Having tried and failed for decades to join the eu, says a seasoned European diplomat, the country is now seeking to enter the West through its mosques. At the opening of the giant new mosque in Cologne last September Mr Erdogan and his religious establishment caused consternation by excluding the local officials who had supported its construction. The following month he unveiled a restored Ottoman shrine in Hungary’s capital, Budapest. The expansion of foreign-dominated Islam in Europe shows no sign of abating, even though the continent’s native-born Muslims will soon outnumber its immigrant ones.

Western responses

Taking back control

Western governments are trying to make Islam their own

Horst Seehofer, the German interior minister and then leader of Bavaria’s Christian Socialist Union, was in a conciliatory mood. Addressing a conference of Muslims in Berlin last November, he publicly reversed his earlier position that Islam did not belong in Germany. It could belong, he told his audience, as long as it embraced German, not foreign, values. His call for assimilation was underlined by the bill of fare at the official reception that evening, which included riesling wines and pork-topped canapés. If Muslims did not like the country’s nudity and alcohol, tutted an official, they could go elsewhere. The drive to integrate Islam on Germany’s terms is the brainchild of Markus Kerber, a top civil servant at the interior ministry and founder of the Islam Conference, a gathering of Muslim representatives that Germany has been holding intermittently since 2006. He wants to wrest control of the country’s mosques from foreign hands, a task he likens to that of Otto von Bismarck, Germany’s first chancellor, when he tried to prise the Catholic church from the Vatican’s clutches in the 19th century. Instead of relying on foreign support, Mr Kerber thinks, mosques in Germany could be funded in the same way as Christian and Jewish places of worship: through a voluntary religious levy on registered members of the faith. Foreign imams should be replaced by German ones, who would be trained at the new Islamic-theology departments that some of the German Länder have established at a handful of universities. Within a decade, Mr Kerber hopes, imams will need German certificates to be able to officiate. Across the West, governments are developing ways of addressing mounting public concern. The run of jihadist attacks (albeit by a small fringe of extremists) and public resistance to mass Muslim migration have helped propel far-right movements into power across Europe. Policies initially designed to focus on security breaches have broadened, first to curb support for and contact with violent extremism and then to counter extremism of all kinds. Many Western leaders, having previously encouraged multiculturalism and diversity, now echo Mr Seehofer’s call for Muslims to adapt their faith to Western norms.

Hands on or hands off?

Security remains a key element. Intelligence agencies monitor known extremists. Parliaments have passed laws making it a criminal offence for their countries’ citizens to fight abroad. Some radical preachers have been expelled or jailed. Dozens of mosques have been closed down. But policymakers are also using other branches of government to tackle what a German official calls “the biggest exogenous influence on the West”. Rather than rely on foreign governments to cater for the needs of their Muslim residents, many Western policymakers now prefer to draw up their own strategies. “We’re fed up with their religious preachers,” says a Belgian security official. “Their sermons are never about being European and always about being Turkish. It turns [the Muslim communities] into a ghetto.” He is even more concerned about the sway held by Saudi Arabia. It is easy to blame foreign management of Islam; harder to tailor a workable alternative. After the jihadist attacks on London’s transport system in 2005, successive British governments tightened up on their laissez-faire approach to Islam in Britain and became more interventionist. In 2007 Tony Blair, a Labour prime minister, unveiled a programme that initially tried to build local partnerships with non-violent Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafist groups to rein in the violent ones. As jihadist attacks spread in Europe, a Conservative government greatly expanded the definition of extremism and made it clear that it would support only liberal Muslims. France has long struggled to reconcile its desire to keep Islam out of the public domain with a growing wish to control it. In 2016 its then prime minister, Manuel Valls, labelled the religion a problem, but found that the principle of laïcité (secularism in public affairs) and a law from 1905 stating that “the republic shall not recognise or subsidise any religion” prevented him from tackling it. The current president, Emmanuel Macron, is considering relaxing that law and supporting the creation of an independent foundation to manage Muslim affairs. The new body, the Muslim Association for French Islam (AMIF), aims to raise funds by issuing licences for France’s (currently unregulated) market in halal food and permits for French Muslims to go on the annual haj (pilgrimage) to Mecca. Proceeds will be used to pay imams and vet them for radicalisation or anti-Semitism. “It will make Islam better accepted in France,” says an AMIF organiser. The European country with the most experience of state supervision of Islam is Austria. When the Austro-Hungarian empire pushed the Ottomans out of the Balkans in 1878, a substantial Muslim population was left behind, mainly in Bosnia. As was customary, the victorious soldiers ransacked the mosques, and the Catholic church built a cathedral on the ruins of the Ottoman barracks in Sarajevo.

But instead of expelling Bosnia’s Muslims, Emperor Franz Joseph I formally accepted them as his subjects. He set up a new body, the Islamic Community, to minister to Muslim affairs, and appointed a mufti to run it. A law passed in 1912 made Islam an official religion and put it on a par with Christianity. It survived Austrian governments of many colours until 2015, when an incoming right-wing one amended it to curb Turkish influence and ban foreign funding of mosques. Last June 40 Turkish imams were expelled and seven foreign-run mosques ordered to close. Newly arrived refugees now have to take a compulsory course in Austrian values, and the religious curriculum for Muslim schoolchildren has been revised. The official at the education ministry in charge of the overhaul is the picture of Muslim orthodoxy; not a wisp of hair pokes from under her headscarf. But she is an ardent supporter of strong measures to end “Muslim self-isolation”. She is in favour of the government’s closure of Muslim kindergartens, a ban on headscarves for girls under ten, and encouraging Muslim girls to attend swimming lessons and go on school trips. Her new curriculum requires students to write sermons opposing forced marriage and demonisation of homosexuals rather than learn religious texts by rote. “If we don’t contextualise our religion, we’ll lose our children,” she says. Many Muslims respond well to efforts to include them. The government’s integration centre in the heart of the Austrian capital, Vienna, is lined with old photographs of Egyptian women in bikinis and unveiled Afghan students before the Islamists dominated public space. The mixed class of young Iranians and Afghans attending the one-day course in Austrian values listen intently. A translator relays the lessons on Mozart’s sonatas, Gustav Klimt’s paintings, Austria’s descent into Nazism and its post-war recovery, but most of the class speak German well enough not to need him. Some volunteer to give presentations in their host country’s language on democracy, the dangers of anti-Semitism and the protection of gay rights. “If only all Austrians had to sit [this test],” says the instructor.

Of booze and burqas

Austria has joined France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, Hungary and Bulgaria in banning the burqa, as have a number of cities and regions. Denmark has gone further than most. The country has one of western Europe’s lowest rates of jihadist attacks, but fear of Islam is pervasive. Last year the right-wing government introduced a rule requiring children from designated poor districts inhabited mainly by immigrants, which it calls “ghettos”, to attend a day-care centre for 25 hours a week from the age of one (as almost all Danish children do). Another recent law requires new citizens to shake hands at naturalisation ceremonies, even though some Muslims oppose touching members of the opposite sex on religious grounds. Government subsidies to Muslim (but not Christian or Jewish) schools have been cut, and some have closed down. To many Muslims and Western liberals, such policies seem counterproductive. Muslims feel stigmatised, alienated and defensive. Unlike in other Western countries, young Muslims in Denmark are more observant than their elders. After a century of separation of church and state, many worry, too, about state intervention in religious affairs. Some Muslims fear that government efforts to form representative bodies will be dominated by large communal organisations. Others warn against trying to replicate government controls on Islam that have proved stifling in much of the Muslim world. “If you opt for state-sponsored Islam, you’re no better than Iran,” says Muddassar Ahmed, who leads Concordia, an international caucus of young Western Muslim leaders. Letting Islam develop organically as a matter of personal faith, he says, would be more in keeping with the norms of Western modernity.

Jihadist Islam

Hollow victories

The destructive power of a violent fringe

No place in Europe has done more to nurture Europe’s jihadists than the quaint neighbourhood of Molenbeek in Brussels. Some of its youth planned the Paris attacks in November 2015 and the suicide-bombings in Brussels five months later. Molenbeek is now quiet, but Johan Leman, a veteran social worker who knew one of the bombers, finds the lull almost more unnerving than the attacks. Since the jihadists first appeared in the 1990s, he twice thought they had gone, but they struck again years later and more violently than before. “They are incubating again,” he says. The overwhelming majority of Muslims is law-abiding and has no truck with Islamic State (is). Of the 30m of those who live in the West, just 7,000 joined the terrorist organisation’s battles abroad. Even fewer perpetrated violence in Europe. Yet militant groups like is have a disproportionate influence on how the West sees Muslims. An opinion poll by Pew in 2017 found that is caused more concern in the West than any other international issue, above climate change and the global economy. A tiny radicalised fringe group is tarring Islam in the West with an undeserved brush. Jihadism has its origins in the liberation struggles against Western colonialism in the Middle East. Religious leaders in Algeria, Libya and Palestine waged jihads against their French, Italian and British overlords in the 19th and 20th centuries. Defence of Islam was just one of the reasons militants picked up arms to push out the West. Once the foreign armies had gone, those hostilities faded. From the 1950s onwards Western governments and Islamists had a common foe: the pro-Soviet nationalist regimes that took power in the Middle East. In the 1980s they joined forces to remove the Soviets from Afghanistan. Back then Abdullah Azzam, the founder of al-Qaeda, an army of predominantly Arab Islamist volunteers in Afghanistan, got an American visa to tour America’s mosques to raise funds for jihad. After Osama bin Laden took the helm, many of his henchmen found asylum in Europe. But the relationship soured. Soon after the Soviets had left, American forces moved into Saudi Arabia to oust Iraq from Kuwait. Allies became enemies again, culminating in the attacks of September 11th 2001 when al-Qaeda used hijacked planes to fell the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Centre and part of the Pentagon in Washington, dc. America declared war on terror, invaded Afghanistan and Iraq and attracted a fresh generation of recruits to confront them. Al Qaeda spread underground. In 2014 is swept the heartlands of the Middle East, mesmerising Muslims and non-Muslims alike with the speed and barbarity of its victories. Al-Qaeda had been focused on getting the West out of Muslim lands and ending its support for Arab dictators it deemed apostates and stooges. is tried to carve a “caliphate” out of the Middle East’s failed states as a base and prepared for global expansion. Its view of the world, rooted in classical texts, was beguilingly simple. Those it had conquered were dar al-Islam(the territory of Islam). Those yet to be conquered were dar al-harb (the territory of war). Through multiple channels, from pulpits to social media, it launched a worldwide call for support. This ideological shift triggered a clear change in recruitment. Al-Qaeda had aspired to create an intellectual elite and its disciples were almost all Arabs. is appealed to all Muslims. Their first task was to cement the caliphate. Those who could should make the hijra, or flight to the new state, emulating the followers of the Prophet Muhammad who left pagan-ruled Mecca for a new Islamic state in Medina. Those who were unable to make the journey should fight behind enemy lines.

The romance of radicalism

For a small, radicalised segment of the Muslim population, is had a magnetic appeal. A disproportionately large number of this group came from the West. Muslims in western Europe account for only 1.5% of the world’s total Muslim population of 1.8bn, but made up more than a sixth of the 30,000 foreign fighters who joined is after its declaration of the caliphate in 2014. Terrorism experts estimate that one-third of the total have been killed, one-third are still at large and, worryingly, one-third have returned to their home countries. Still, the vast majority of is attacks in Europe and America were carried out by Muslims who had never been to Syria or Iraq but chose to fight from home. Of 455 jihadist terrorists, 70% were citizens of the countries where they perpetrated the attacks, and half were native-born. Earlier jihads, in Algeria and Bosnia in the 1990s, had taken place on Europe’s doorstep. The number of supporters they attracted were smaller, but for some young Muslims they promised adventure and heroism, akin to the Spanish civil war which drew European romantics in the 1930s. “I don’t see myself as an extremist,” says Ismail Royer, an American who converted to Islam and went to fight in Bosnia and Kashmir. “I see myself as having been naive, romantic, a Don Quixote kind of guy.” He renounced violence while in jail in America and now works for a Washington-based ngo promoting religious freedom. Mr Royer had been radicalised by jihadist preachers who were born in America but had grown up in the Middle East and later returned with a new ideology. Others were swayed by Arab veterans of the Afghan war who won asylum in the West in the 1990s.

France also unwittingly played a part in disseminating the ideology. It feared that the Algerian civil war then in progress might spread to Muslims with Algerian roots in France. After two jihadist attacks, including one in Paris in 1994, it arrested many of its barbus, or beards, causing an exodus to Belgium, Germany and Britain. Although al-Qaeda had little interest in Western Muslims, other Islamist groups courted them. Hizb ut-Tahrir, the Liberation Party, was born in Palestine in the 1950s, but acquired a mass following in Britain and Denmark with its call to restore a global caliphate. An offshoot, al-Muhajiroun, more openly espoused violence. Its charismatic preachers packed London’s 8,000-seat Wembley Arena, urging followers to boycott Western democracies and eschew secular lifestyles as a manifestation of kufr(unbelief). Other conservative schools, such as the Salafists, were less political and mostly rejected violence, but advocated keeping away from non-Muslims. Some Salafist scholars spread hate of non-Muslims of all kinds. In some parts of Europe such teaching dovetailed with an already divided society. But it had broader reach, too. Unlike the foreign-run mosques of the first generation, it packaged Islam in the vernacular. On the pretext of recovering the pristine faith of the Prophet, Salafists purged the first generation’s traditional customs that second-generation Muslims, and converts raised in the West, found so alienating. “They offered Islam for those who had no tradition,” says Azhar Majothi, a British Muslim scholar of Salafism at Nottingham University. Kubra Gumusay, a German Muslim writer, concurs. “Religious identity was often used by native-born Muslims as a tool to dissociate themselves from the ethnic identities of their parents,” she notes. In particular, it liberated girls constrained by their parents’ traditions. Many teenage girls were driven to is’s caliphate abroad by dreams of female activism, as well as the desire to escape arranged marriages. Some 17% of Europe’s foreign fighters were women. An assertive Islamic identity particularly appealed to second-generation Muslims who did not feel quite at home with Western ways. “They were rebelling against both their parents and society,” says M’hammed Henniche, a communal leader in Saint Denis, a suburb of Paris. Not many preachers openly advocated violence in the West, and many Salafists opposed breaking the law. But when is surfaced, it found a constituency whose ear could be tuned to their message. Second generation migrants had already perpetrated several attacks.

In 2004 Mohammad Bouyeri, a Dutch-born Berber Islamist, killed Theo van Gogh, a film-maker who produced documentaries criticising Islam. The note left on his body read, “Europe, you’re next.” In 2005 three second-generation British Muslims and a convert blew themselves up on London’s public-transport system, killing 52. Half of the jihadists who carried out attacks in the West since 9/11 were radicalised online, according to New America, a thinktank based in Washington, dc. Some preachers streamed self-erasing lectures on Snapchat. Their messages were particularly lethal in America, given the ready availability of weapons. Since 2013, 87 people have been killed in terrorist attacks there. “We’re bigger than ever,” insists a Danish organiser of Hizb ut-Tahrir. “You just can’t see us.” Germany’s spy agency agrees. It estimates that the number of Salafists providing a pool of recruits for jihadists has increased from under 4,000 in 2013 to more than 10,000 today. Preachers ousted from their pulpits whispered invitations to meet privately to worshippers at Friday prayers. And increasingly gyms and schools became recruitment centres. Friends plotted their hijra from gritty estates and stifling parental control in the schoolyard. A dozen left one summer holiday from Campus de Brug high school in a Brussels suburb. In Dinslaken, a workingclass town in Germany’s Rhineland, Lamya Kaddor, a high-school teacher of Islamic studies, discovered one day that her pupils had gone. “They knew nothing about Islam,” she says. “They took drugs, went to parties, had girlfriends.” Europe’s prisons provided another source of recruits. They contained large numbers of Muslim inmates convicted for criminal offences who were already well-versed in skills like smuggling and gun-running. Two-thirds of foreign fighters in Germany and the Netherlands had a criminal record. Jihadism and petty crime were so intertwined that some used the term “gangster Islam”. Muslim chaplains found themselves being turned away when they tried to visit prisoners of their faith. The suspension of Saudi funding, under Western pressure, also encouraged some Salafist groups to find less legitimate sources of finance. is had a particular knack for penetrating the underworld and giving criminals a cause. Infidel assets, explained is’s leader in Germany, were ghanima, or spoils of war. Khalid Zerkani, an is recruiter from Morocco, followed the hashish trail from farms deep in the country’s Rif mountains to the waystations in Europe where many of the Rif’s Berbers lived, and eventually settled in Belgium’s Molenbeek. “He was a father figure,” says a local social worker. “He would ask about your future and explain how you could find a better job, a better salary and a just society under the sharia. And your sins would be forgiven.” Mr Zerkani was arrested in 2014. One of his recruits, Ibrahim Abdeslam, owned Les Béguines, a gay bar in Molenbeek that was repeatedly raided for drugs. He sold it six weeks before donning a suicide-vest and blowing himself up in a bar during the Paris attacks in November 2015 that killed 130. When his brother, Salah, who planned the getaway, was eventually captured in March 2016, his friends retaliated four days later with attacks on the Brussels metro and airport, killing 32. Les Béguines was shut down soon after the Brussels attack, but would-be jihadists can easily find other places to meet. For some, the gangsters still carry street-cred. At L’Epicerie, a Molenbeek warehouse turned into a theatre by locals of Moroccan origin, teenagers offer their rendition of a parents’ evening. “You’ve been playing truant. Why?” asks the teacher in the play. “I went to Afghanistan,” shrugs the boy. The audience laughs. For most Western Muslims the appeal of jihadism reassuringly tails off after two generations. Only 7% of attacks in the West were perpetrated by grandchildren of immigrants. But police fear a new wave of violence when the current crop of radicalised prisoners are released. If places like Molenbeek are to break the cycle of jihad, young Muslims will need to feel properly at home in the West.

Fusing Cultures

West-eastern divan

How Islam is adapting to life in the West

People are of two types in relation to you,” Imam Ali, the prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law and one of his first caliphs, or successors, is reputed to have said. “Either your brother in Islam, or your brother in humanity.” The Shia community of Mahfil Ali in north London tries to turn word into deed. Women often open services with a prayer. Sermons are in English. For the past decade the community has gone to the local church on Christmas Eve to attend midnight mass. Most ambitiously, it is turning its two-hut mosque into a £20m ($26m) Salaam (Peace) centre, complete with sports facilities, a restaurant, a theatre and a public library. There is talk of making a prayer space for Christians and Jews. “We want to nurture the community that nurtured us,” says a local leader. Mosques in the West have come a long way since migrant workers rolled out plastic mats in their back rooms. A new generation of cathedral mosques has brought Islam out of Muslim districts into the public arena. Instead of traditional structures with in wardlooking courtyards, their architects now design wide staircases that connect to the street. Sports facilities draw in younger Muslims who may have lost interest in the faith, as well as non-Muslims. The Islamic Centre of Greater Cincinnati, spread over 18 acres (seven hectares), is one of many in America that feels more like a country club than a mosque.

Christian and Jewish teams compete in its basketball league. Foreign organisations, Western governments and jihadists have all sought to speak for and mould Islam in the West, but the more established the faith becomes there, the less truck it wants with any of them. Of the three generations that have grown up since Muslims arrived in the West in the 20th century, the third is the most stridently opposed to government interference, be it foreign or Western, and to jihadist propaganda. As time passes, the old ties loosen. In most of the West, unlike in Muslim countries, no licence is currently needed to become an imam. Instead of a faith shaped from outside, millennial Muslims are creating something unprecedented: a do-it-yourself Islam. That makes the religion frustratingly messy, but also diverse, dynamic and fluid. It is fragmenting into myriad interpretations, permutations and sects. Each by itself might be small, but collectively they are acquiring a critical mass that is pushing the faith’s boundaries. Western Islam covers the full spectrum of Islamic traditions, from the most conservative to the sort that considers Islam a culture but no longer a faith, and everything in between.

The four schools of Western Islam

To outsiders, the Salafist strand of the faith looks deeply traditional and unwelcoming. Its members wear Islamic dress and send their children to segregated Muslim schools. Boys in white tunics shiver in the cold. Teachers focus on scripture. But the Salafists insist that much of what they believe chimes with a Western approach to the faith. “Its appeal is like that of Protestant reformation in Christianity,” says Yasir Qadhi, America’s bestknown preacher, who studied with Salafist masters. “It gives the individual direct connection to the text without going through a cleric or priest. It’s intellectually empowering.” Though German officials, among others, have cut off dialogue, a new generation of Salafists is experimenting with greater openness. Searching for allies to stem secularism’s advance, Salafist imams engage in interfaith dialogue with like-minded conservatives of other faiths. The rapid influx of converts, too, has forced them to find ways to deal with their non-Muslim relatives. For role models, preachers look to the first Muslims in Mecca 1,400 years ago. They were also converts but kept their ties with their pagan families. And when they were persecuted, they embarked on the first hijra, or migration, and found refuge with the Christian rulers of Abyssinia. From his home in Memphis, Tennessee, Mr Qadhi plans to launch a new Islamic seminary later this year, staffed exclusively by Western lecturers. The teaching there, he says, will be “post-Salafist”, concentrating on the essentials. “While old-school Salafists are arguing over the minutiae of Islamic law, their children are debating whether or not God even exists,” he adds. The second strand of the faith, political Islam, has long advocated engagement with non-Muslim society, not least to defend the interests of the umma, or Muslim community. Its main organisation, the Muslim Brotherhood, began as an armed anti-colonial movement in the Middle East. But chased into exile, its leaders have established a host of offshoots which profess loyalty to the West and praise its democratic systems (to the horror of the Muslim rulers they fled). It can be highly pragmatic. At a class at the Institut Européen des Sciences Humaines in Paris, Europe’s largest Muslim college and a bastion of Brotherhood orthodoxy, a female lecturer emphasises the flexibility of the sharia, or Islamic law, and its guiding principle of maslaha, or communal interest. Another of the Brotherhood’s institutions, the Dublin-based European Council for Fatwa and Research, is rewriting orthodox precepts. Its jurists have approved mortgages, despite the Islamic prohibition on interest. They have ruled that female converts to Islam can keep their non-Muslim husbands. And some increasingly turn a blind eye to ways of life hitherto deemed deviant. “I’m not God. It’s his business. I don’t interfere,” says Taha Sabri, the imam of an Islamist mosque in Berlin. If the Brotherhood gives Islam a Western hue, liberals, the third strand, give their Western lifestyles an Islamic one. For more than a generation, Bassam Tibi, a devout academic of Syrian origin at Göttingen university in Germany, has campaigned for “euro-Islam”, which by his definition is rooted in the principles of the Renaissance, Enlightenment and French Revolution. The faith, he says, has to adapt to its new environment, just as it did when it spread elsewhere in the world. “Africans made an African Islam and Indonesians made an Indonesian one,” he notes. “Islam is flexible and can be European.” A few congregations of women-led mosques have surfaced in the West beyond the ivory towers of academia. Some are women only, others mixed. Weekly prayers are often conducted on Sundays for members unable to leave work on Fridays. In 2008 Rabya Mueller, a former Catholic nun who converted to Islam, formed the Islamic Liberal Bund, modelled closely on liberal Judaism, and has begun leading prayers. Together with Lamya Kaddor, a German woman with a Syrian background, she is replacing Islam’s patriarchal baggage with gender equality and a commitment to gay rights. Much of their work, she says, involves marrying Muslims and non Muslims of either gender. On Twitter, @queermuslims advertises prayer meetings for homosexual adherents of the faith. A training centre for gay imams has opened in France. At the far end of the spectrum, a fourth strand wants to dispense with the religion altogether. In November six German academics, including one non-Muslim, formed the Secular Islam Initiative to promote “a folkloric relationship to Islam”, according to one of its founders, Hamed Abdel-Samad, the son of an Egyptian imam and author of a critical biography of the Prophet Muhammad. The organisation is still at the fledgling stage, but it may express the views of a surprising number of Muslims born in the West. According to a German government survey, only 20% of the country’s Muslims belong to a religious organisation. Many of the rest lead secular lives. The number of lapsed Muslims in France is probably even higher than in Germany, particularly among descendants of north Africa’s Berbers, many of whom have long viewed Islam as a fig leaf for Arabisation. Half the men of Algerian origin in France marry outside the faith, and 60% of those of Algerian parentage say they have no religious affiliation. In America the Pew Research Centre estimates that 23% of Muslims no longer identify with the faith. “We’re facing the same problem of assimilation as the Jews,” says an imam in Dearborn, Michigan.

Thinking the unthinkable

Mosques seeking to rejuvenate their flock are having to adapt to changing sexual practices, too. Half of America’s Muslim students, male and female, admit to having had premarital sex, according to a study in 2014. “When I began teaching in 2003, no girl would admit to having a boyfriend,” says Ms Kaddor, who until recently taught religious studies for Muslims in a Rhineland school. “Now, some openly say they’re bisexual.” Muslim dating apps abound. “Find a beautiful Arab or Muslim girl on muzmatch,” promises one that claims a million users, complete with an optional chaperone feature. Women are also increasingly demanding a say, not least because they are now typically better educated than men. The number of women on mosque boards is still small but growing, even in orthodox communities. Inside the prayer hall, women, originally confined to the gallery, are moving to the back of the ground floor and sometimes down the sides. In many Black American mosques men and women share the same hall. Prejudice against homosexuality remains strong but is retreating. Among British Muslims over 65, 76% want to ban the practice; for those aged 18-24, the proportion is 40%. Adherents of all four strands often change allegiance. Mr Abdel-Samad was briefly a Muslim Brother before converting to secularism. Many Salafist preachers were nominal Christians who trod the path in reverse. Such cross-fertilisation does not always breed understanding. Imams deviating from orthodoxy risk expulsion from their mosques. Abdel Adhim Kamouss, a Salafist preacher in Berlin, has been ousted from two mosques for asserting that the Prophet did not condemn homosexuality or shaking hands with women. Mr Kamouss is one of several people interviewed for this report to receive a fatwa sentencing him to death for apostasy. In the suburbs of some British cities Muslim shopkeepers are forced to close before Friday prayers. And women can still become victims of honour crimes in conservative enclaves such as Dewsbury in northern England. Optimists say such violence is a sign of desperation. In France the last known honour crime was committed two decades ago. Across the West Muslims turn out to vote in greater numbers than the rest of the population and increasingly interact with non-Muslims. For many of the younger ones, divisions of sect, ethnicity and religious observance are less and less relevant. In short, given a range of choices, Muslims in the West increasingly see Islam more as a matter of personal choice than a creed guided by government, whether at home or abroad. “The younger generation has won the battle,” says Olivier Roy, a French author on Islam in the West. Arab governments sometimes berate their Western counterparts for not doing enough to curb extremism, by which they often mean curbing their exiled dissidents. In fact, Western governments do monitor hate speech and support for terrorism. But viewing Islam primarily through a security prism distorts relations between Muslims and non-Muslims in the West. Muslim inclusion in local decision-making can break down prejudice but often faces resistance from communities. Jennifer Eggert, a Muslim expert on terrorism, tours London mosques arguing for Muslims to play a bigger part in countering terrorism. The New York Police Department overcame communal mistrust by creating a Muslim Officers Society, the first in America. This has helped increase police recruitment among Muslims from fewer than a dozen in 2001 to over 1,000, says its founder, Adeel Rana. The inauguration last month of America’s first two Muslim congresswomen may also help normalise Muslim participation at all levels of society. Integrating Islam more into national histories could play a part, too. In some British mosques imams pinned poppies on each other to mark the centennial of the first world war and remember the hundreds of thousands of Muslims killed in battle. But their sacrifice is rarely commemorated at national level, contributing to the feeling that Muslims remain outsiders. Now “we are creating a generation not of foreign fighters but of foreign citizens,” says Khalid Chaouki, a former mp in Italy’s parliament who runs the country’s largest mosque in Rome. Cultural programmes, too, can cross communal boundaries. When the Benaki Museum in Athens began offering school tours of its Islamic art collection, an mp accused it of spreading the culture of terror. A decade on, the museum has expanded the programme to include interactive tours of life in Ottoman Athens. “We’re filling a big gap in our history that most schools skip over,” says Maria-Christina Yannoulatou, the head of the museum’s education department, referring to 450 years of Muslim rule that Greece omits from its curriculum. “We want to challenge taboos and show the ordinary lives that heroic histories obscure.” Religious leaders are also seeking to bridge divides. Many priests work hard to counter far-right narratives, accusing anti immigrant politicians of betraying Christian ethics. Many churches double as sanctuaries for refugees. Some synagogues as well as churches in America host Muslim Friday prayers for congregations lacking a space to worship. In the same vein, after a right-wing gunmen fired on a Pittsburgh synagogue in October, Muslims packed the vigils, sent tweets of condolence and spoke at events on anti-Semitism. In Germany’s election in 2017 church-going voters were three times less likely to vote for the far-right AFD party than secular ones. Having settled in the West for the third time in history, this time in a different role, Islam seems destined to stay. The journey so far has not been easy. But a third generation of Muslims now seems set to become a permanent part of a more diverse, more tolerant Western society—as long as that society continues to nurture those virtues.